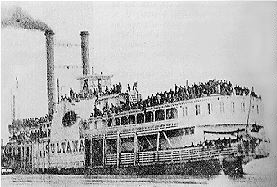

---The great American Civil War was over. The Union soldiers were going home. Some had been lucky; they had survived bullets and hunger, disease and surgeons. Some, a very lucky minority, had even survived the infamous Confederate prisons at CAHABA (Alabama) and ANDERSONVILLE, (Georgia).

They were brought to Vicksburg to begin the long journey home to places like

Knoxville, Tennessee; Madison, Indiana; and Cincinnati, Ohio. Most were walking skeletons; many had to be carried on litters. All were in high spirits. About 2,400 of them were loaded at Vicksburg onto one small steamer, the SULTANA, like so much baggage. Within 48 hours nearly 1,800 of them would be dead in the Mississippi River above Memphis- either drowned or blown to bits by the explosion of the ship's boiler. For some, death was merciful; for others,

unspeakable agony. It was 2 AM, April 27, 1865, and this would stand as the

greatest maritime disaster of all time in America.---

April 26, 1865, we boarded the steamer Sultana and everything went smoothly until we reached Memphis. There two hundred and fifty hogshead of sugar were unloaded, many soldiers assisting the crew, thus earning a little money, a fair supper and, for those who wanted it, all the whiskey they could drink. From there still northward the steamer plowed her way through the night, her living freight wrapped in slumber and no noise, except the steady puffing of the engines, disturbed the sleepers. About 2 o’clock in the morning of April 27th, the widely chronicled explosion took place. For a moment the darkness of the night was intensified and then came the screams and groans of the injured. Andy McCormack, Thomas Laboyteaux and myself were sleeping together on the hurricane deck about halfway between the pilot house and the bow of the boat, dreaming of home and friends. The first thing I knew of the explosion I was standing on my feet looking right down into the boiler room. The whole of the vessel, amid-ship, was torn in pieces; fire quickly followed the explosion and the red glare of the flames disclosed a scene of terror and tragedy. My first thought was, ‘How can we save ourselves?’ Andy McCormack was sleeping soundly and only partly aroused by the explosion, he asked ‘where is my blanket?’ I told him I didn’t think he would ever need a blanket again and we would be lucky to escape with our lives.

April 26, 1865, we boarded the steamer Sultana and everything went smoothly until we reached Memphis. There two hundred and fifty hogshead of sugar were unloaded, many soldiers assisting the crew, thus earning a little money, a fair supper and, for those who wanted it, all the whiskey they could drink. From there still northward the steamer plowed her way through the night, her living freight wrapped in slumber and no noise, except the steady puffing of the engines, disturbed the sleepers. About 2 o’clock in the morning of April 27th, the widely chronicled explosion took place. For a moment the darkness of the night was intensified and then came the screams and groans of the injured. Andy McCormack, Thomas Laboyteaux and myself were sleeping together on the hurricane deck about halfway between the pilot house and the bow of the boat, dreaming of home and friends. The first thing I knew of the explosion I was standing on my feet looking right down into the boiler room. The whole of the vessel, amid-ship, was torn in pieces; fire quickly followed the explosion and the red glare of the flames disclosed a scene of terror and tragedy. My first thought was, ‘How can we save ourselves?’ Andy McCormack was sleeping soundly and only partly aroused by the explosion, he asked ‘where is my blanket?’ I told him I didn’t think he would ever need a blanket again and we would be lucky to escape with our lives.

Andy turned around and started away. I moved to the bow of the boat and saw dozens of men jumping into the river. So many were taking to the water that I feared to follow, lest I should be dragged down by the clutch of some drowning victim. Looking about, I seized a large rope and slid to the lower deck, where I stood until the Fierce heat drove me over the side. I threw a door into the water and on that floated two or three miles, but strugglers in the water kept grasping the door and turning it over so that I abandoned it and swam down the river alone, until I overtook some fifteen or eighteen men on a gangplank, whom I joined. Their combined weight sank them to their necks in the water and the gangplank constantly turning, threw many under the water, never to reappear.

The river from the boat to Memphis, was full of struggling men and dead bodies. Myself and a sergeant f a Michigan regiment caught some driftwood and tried to raft ourselves ashore, but the men were so excited we could do nothing. When we came around the bend and saw Memphis, we knew where we were. We drifted past the landing which was crowded with people from the city. Opposite Fort Pickering, two men in a skiff rowed out to within twenty or thirty feet of us, but feared to approach nearer, lest the men, in a scramble for safety, should overturn the boat. The Michigan sergeant and myself (I was a good swimmer) swam to the skiff and were taken ashore.

Numbed by the cold and exposure, we could hardly walk. Our rescuers took us up the steep banks of the Mississippi river and into the fort and gave each of us a half pint of whiskey and supplied each of us with breakfast and lent us clothing, until such time a we could be outfitted by the government, which was done on the following day at the hospital to which we were removed from Fort Pickering. From the hospital, we were taken to the Soldiers’ Home, where we remained until taken aboard the U. S. Mail boat, bound for Cairo, Ill. Thence we went by rail to Mattoon, Ill., where the citizens tendered us a reception. From Mattoon we went to Indianapolis, and thence scattered to our homes. This home-coming was to me, as no doubt, it was to all, the happiest day and moment of my life.

♦♦♦

Andrew Jackson McCormack was born June 26, 1846, on the farm of his parents, Melon and Mary McCormack, near the town of Cadiz. He had three brothers who served in the Civil War, for one of whom, John R. McCormack, Post #403, G. A. R. Cadiz was named.

Andrew J. McCormack enlisted in the Union Army in 1863 in Company E, Ninth Indiana Cavalry, and was mustered into the service of the United States as a private, January 8, 1864. The regiment served with the Army of The Cumberland and was engaged in the military operations against the advance of General Hood’s Confederate forces towards Nashville, Tenn.

|

Henry County Genealogical Services

Henry County Genealogical Services